- Throwing Irregular Shapes

- Posts

- Combat, Utility & Sandboxing

Combat, Utility & Sandboxing

Thinking about decision-making in 5th Edition D&D

Last time, I said I wanted to talk about combat encounters, non-combat encounters, and the semi-sandbox situation that is the Heliomar game. And for once in my newsletter-writing life, I’m actually going to do that, instead of having something else which entered my head in the meantime take over instead. Though, as per usual, this is some rambling stuff.

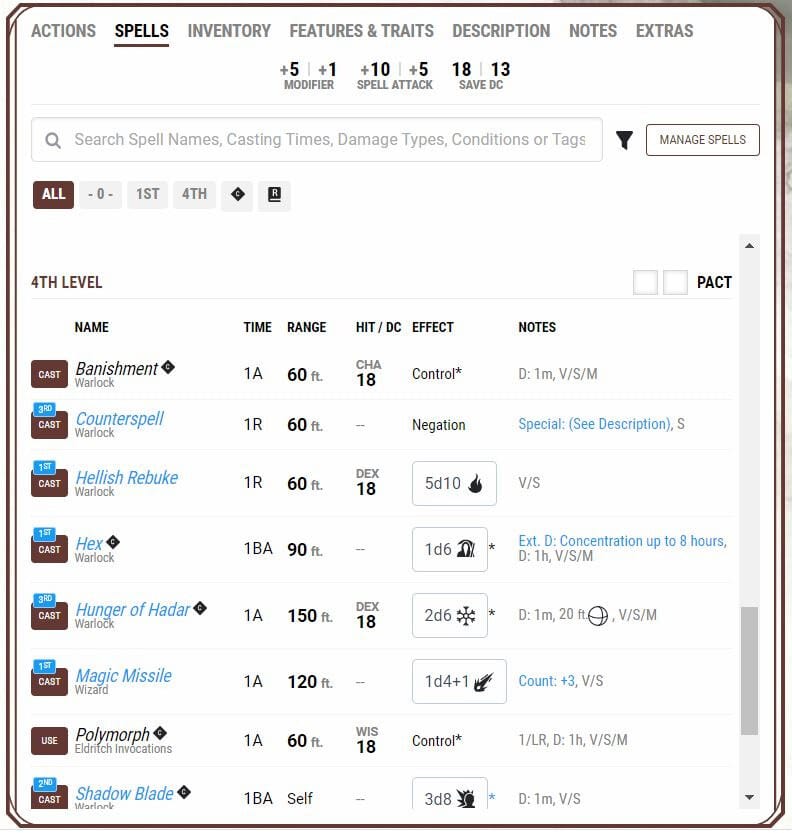

In order to talk about this, though, I need to chase off after some spellcasting stuff, because it’s the best example of a process. 4th Edition D&D did, as with most things, some weird stuff with utility spells. There were, for example, teleportation powers you could use in combat, which would only transfer you over line-of-sight distances, and teleport spells that were rituals, which could actually transport you over longer distances; travel spells, as it were.

5E has gone back to the state where all these things are spells, and there are ways to do short-distance teleports at lower levels, and long-distance at higher levels, but they all use the same resource of spell slots. There’s a beautiful degree of balance among the various travel spells, too; and it had escaped my notice until recently how well druids do in that. Let me expand, before I come back to the combat/non-combat stuff.

The relevant spells are the 5th level teleportation circle (and later the 7th level teleport) for the wizard and the 6th level spells transport via plants and wind walk for the druid. The only equivalent for the clerical end of things is the 6th level word of recall, which just isn’t as good. For completeness, I should also mention plane shift and gate, both of which function more in the context of planar travel. And yes, I know sorcerers and warlocks and bards and such have access to some of these.

So, teleportation circle only takes you to a specific point for which you know the “address”. The way I run this, the addresses of teleportation circles can be shared, and most of them are closely guarded, because it’s an easy way for someone to drop a powerful group of antagonists directly into your fortress or stronghold. For this spell, the caster does not have to travel. Teleport allows the caster to target anywhere on the same plane of existence, but comes with some possible targeting errors - depending on whether a place is “very familiar”, “seen casually”, “viewed once”, or known only via description, one could end up on target, off target, in a similar area, or have a “mishap” go off instead. All of this can be circumvented by having an object taken from the target location in the last six months, which is why wizards in both my current campaign settings tend to have large collections of very carefully labelled rocks. For teleport, the caster has to travel as well.

Now, the druid spells: transport via plants forms a connection between two plants, one where the caster is, and one they’ve seen before, such that you can step into one and out of the other. The plants must be in the “large” size category, or bigger, which is to say that for the most part, they have to be trees. The caster does not have to travel. Obviously, this has limitations; you’re not going to be able to use transport via plants to get into the Desert Stronghold of the Arid Saltfolk. But it’s otherwise pretty spectacularly useful. Similarly, wind walk allows a party of up to 11, including the caster, to turn into wisps of cloud and fly at a remarkably high speed for 8 hours. A post-it note in my Player’s Handbook holds the calculations from movement rates to actual distance covered: up to 889km before the spell ends. And unlike the teleportation spells, you can see what’s happening in your destination before you get there, and decide where exactly you want to land.

The balance between these is superb. All of them have advantages and disadvantages. But the best thing - from the point of view of making interesting choices - is that these pure utility powers of transport draw from the same resource as the combat spells; spell slots. If you’re an 11th level druid, and you wind walk your party somewhere, then you’ve given up the ability to cast any other 6th level spell that day. And 6th level includes things like heal and sunbeam, both of which can very definitely make the difference between winning and losing a fight.

And then there are the non-combat encounters. 4th Edition really didn’t know what to do with these. It had the concept of “skill challenges”, which basically turned almost anything into “roll dice seven times, and see how many high numbers you get” (I over-simplify, I know). Utility spells, and the choice to use them, and thereby spell slots, turn even the most ordinary encounter into something with strategic weight. Obviously, this isn’t quite as true for the non-spellcasting classes, but many of them have other tradeoffs and choices to make as well. Which brings me back to where I started, and what I actually want to talk about.

There is a perception among some D&D players that any given encounter is a combat encounter, or it is a non-combat encounter. I’m not keen on this. First, I’m not awfully happy with the division of the game into distinct encounters (also, it turns out that if you type “encounter” often enough, it really does lose all meaning). Second, I want my worlds to feel like the people in them - the player characters in particular, but NPCs as well - have free will (philosophical considerations aside). So while I will occasionally have cases where there just is combat (ambushes, guardian undead, etc.) and equally occasionally have cases where combat isn’t happening (conversation with an archmage, the Druid Council chamber in session), most situations could go either way. There’s a complicated mix of who’s playing in that session, who’s paying attention at the beginning of the encounter, what the group wants, how close we are to the end of the usual session duration, and so forth. And, most relevant here, how many spell slots the casters still have.

Incidentally, there’s an interesting (and completely unverified) datum I came across recently: the balance of difficulty of encounters in 5th Edition assumes that groups will have 8 encounters between long rests. This goes some way towards explaining why my groups, in both campaigns, waltz through “deadly” situations regularly; they are at the most taking on 3 encounters before stopping and having a good night’s sleep. Stuffing 8 encounters into a day seems kind of mad in narrative terms; some back of the envelope calculations say it’d take about 30 days in-game to go from 1st to 20th level, and really, that’s just weird.

Back on topic, Drew. So: this one resource, spell slots, governs a lot of what can and cannot happen in the game. In a recent session of the Heliomar campaign, the cleric and the druid were very, very close to being out of spells. Anna’s tank kind of depends on there being a healer around, for instance, and that healer having spells. And the casters themselves have an ongoing assessment of whether to use the utility spells for exploration, social interaction, campsite creation, or whatever, or to save them for combat. And whether to get into combat. And whether to stick to cantrips or use the spell slots.

(Warlocks, technically, don’t have spell slots)

Heliomar isn’t a game with a pre-determined plot. There are are different things happening in different areas - so far, there’s the West Coast, the Shrikan Hills & Green Bastion, and the Northern Peninsula - and the player group can interact with them or not as they choose. On a micro scale, one encounter at a time, that decision is driven by tactical consideration of spell slots (and, yes, other resources, but I’m not running through all the mechanics of ki and sorcery points, channel divinities, rages per day, et al). On a macro scale… that’s less clear. One player going “I’d like to check out this thing” can move the action from one geographical area to another entirely, and give a completely different direction to the game for a while. We haven’t been playing long enough yet for me to pick out patterns in this, but I have some ideas; I think the macro-level decisions are driven more by the narrative-focused players, while the micro-level ones are pushed by the strategists.

At some point, I think, the macro-level decisions are going to switch from “I’d like to check this out” to “I think we can learn more about X by following up on thing Y”, or by going to place Z, or the like. That’s the point at which the underlying stories will start to become clearer; the ones that I’m beginning to point at in the rumours that I’m supplying to players when there’s downtime, and in various references in in-game broadsheets and other text. But which underlying stories are discovered at all is often driven by whether an encounter is treated as combat or otherwise.

Someone - possibly Ken Hite & Robin Laws in Ken And Robin Talk About Stuff - used the analogy of a literal kids’ sandpit in which there are toys buried. You dig around, you mess with some sand, you find a corner of something. Is it a plastic dinosaur, a miniature JCB, or a shaped bucket for making sandcastles? You’re not going to know unless you dig it out. That is broadly how I am thinking of the Heliomar sandbox, although the toys are in some cases rather large, and will take a while to excavate. But like the bucket, some of them will allow changes to be made to the sandpit itself.

Which is not to say that player characters can’t make changes now. If, for instance, they decide to found their own town, or create a continent-wide guild of tomb-robbers, or decide that they need to destroy the empire, I’ll absolutely willing to roll with that. This is a way in which an RPG campaign really shines; it’s what differentiates it from any other medium of narrative.

I’m really enjoying the current campaigns, and I’m really enjoying thinking about them like this too. The next thing I’m thinking of writing about is providing text information to players, but the gods only know if that’s what the muse will allow. Anyway. Send. Have good games!

Drew.